After school reform march, teachers question what's next

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- About 5,000 people joined in the Save Our Schools March

- One former teacher says she was told to cater to tests, not to students' needs

- The U.S. Education Department: We all must "get much better, much faster"

Editor's Note: Education Overtime is a seven-week series that focuses on the conversations surrounding education issues that affect students, teachers, parents and the community.

Washington (CNN) -- From Race to the Top to "Waiting for 'Superman,' " Americans have been talking about public education reform -- and arguing about how to do it.

On a sweltering afternoon last week, an estimated 5,000 teachers, parents and students went to Washington to make their case for what to do.

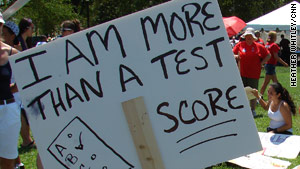

Billed as the Save Our Schools March and National Call to Action, the protest was a loosely organized grass-roots coalition of teachers and parents. Their goals: More equitable funding for schools, more social service supports for families, more local control over curriculum and an end to high-stakes standardized tests.

Organizers said they came to voice their displeasure with the Obama administration's education reform policies.

About 5,000 educators, parents and students gathered at the Save Our Schools march.

After the march, the U.S. Department of Education released a statement: "Reforming America's education system to prepare students to compete in the global economy is one of our country's greatest challenges. While there are different opinions on how best to do that, we all agree that the status quo isn't working. All of us -- the federal government, principals, teachers, students and parents -- need to get much better, much faster."

Some organizations argue that the Save Our Schools movement is taking the wrong approach.

"S.O.S is about deforming education, not reforming it," Jeanne Allen, president of the pro-charter school, pro-school choice nonprofit The Center for Education Reform, said in a press release. "They put up the guise that this is for the families and students, but in truth, these groups want to restrict and remove any power parents have in their child's education."

So, to better understand the motivations of the marchers, CNN caught up with three participants to find out what brought them to Washington.

The teacher turned organizer: Sabrina Stevens Shupe

Sabrina Stevens Shupe, a 25-year-old former teacher from Colorado, remembers the exact moment she first understood algebra, at age 20.

Sabrina Stevens Shupe was a teacher who became an education activist. She helped organize the S.O.S. march.

"Despite being a high-achieving student, it was always so abstract to me in school. But years later, there I was, designing a knitting pattern, and suddenly I got it, and it all became relevant to me," she said.

Stevens Shupe became a teacher three years ago to help students discover what was most relevant to them, and to do so in an active, engaging way.

Then she was told to stop teaching that way and focus instead on the skills most essential for state tests.

"And I thought, 'I can't stand by any longer and let this madness continue,'" she said.

Despite a history of glowing evaluations, her contract was not renewed. She believes it was a retaliatory action for taking a stand against the school's emphasis on narrowed curriculum and test preparation.

After blogging and speaking publicly on the issues, Stevens Shupe became one of the march's central organizers last winter. She helped the organization's online presence through blogs, Twitter and Facebook, which helped mobilize people from around the country.

"We were able to forge a coalition out of isolated groups and individuals, and bring people together from every corner of the country in order to demand a different path forward, a permanent seat at the table," she said. "Before the March, many of us felt demoralized and alone. But now, we recognize that we are part of something larger. And I am so proud to be a part of that."

Once a teacher, now a mom and blogger: Rachel Levy

Rachel Levy is a 38-year-old writer and stay-at-home mom of 8-year-old twin boys and a 5-year-old daughter in Central Virginia. She used to be a teacher.

Levy's decisions to become a writer -- she maintains three blogs, including one about education -- and take a break from teaching were prompted by the same factors that motivated the march.

Actor Matt Damon, whose mother is a teacher, speaks to the crowd during the Save Our Schools march.

"I was wasting far too much of my and my students' time trying to please the testing and data collection gods rather than help children really learn," she said. "But I also realized I had young children and I wasn't yet sure of how to be the teacher or parent I wanted or needed to be."

She said she grew up believing patriotism meant holding politicians accountable, and that drew her to the march.

"To support that, we need a strong and democratic public education system led by well-educated and respected educators who are given enough freedom, time and support to hone their craft," she said in an e-mail to CNN. "And while tests can give us useful information, the sort of fertile learning environment I want for my own children -- and all children -- does not equate quality teaching and learning with simple scores. When people do that, they set the bar way too low for too many of our students."

After the rally, Levy wondered about what the next steps would be.

"I thought it was a powerful, inspiring event, but I wish I'd seen more people there, especially from nearby states," she said. "I live relatively close to D.C. and close to my state capitol. That means I have an obligation as a citizen to take advantage of my proximity to political power. Why were there not more public education stakeholders from D.C., Maryland and Virginia?"

The teacher and filmmaker: Amy Valens

Amy Valens began her teaching career in 1968. The profession had been on her mind since she was 16 and ran a play group in her apartment complex, she said.

Now 64, the Californian recently retired from a teaching job.

One of the goals of the march was to protest the use of standardized tests.

"In recent years I've watched the joy and creativity get wrung out of school for students and teachers alike by a progressively narrower school experience predicated on tests, not children," she said. "So I wanted to stand with others who felt as I did, and to say, 'This is not fair to our children or our country.'"

Valens' own version of activism began a few years ago, when she and her husband produced a documentary film, "August to June," about a year in the life of an elementary school.

She wrote in a blog entry that she sent the film to U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan and received a form-letter response suggesting her school might want to apply for a grant if it had made significant gains.

She wrote that she responded, "If your reference to achieving 'at high levels' means how well our students score on standardized tests, we will not meet your measure. The parents in our programs strenuously object to that approach. ... One visit to our classrooms and it will be clear that we are the exact opposite of a failing school."

RELATED TOPICS

"I've learned over the years what it really takes to ignite the curiosity of a child," Valens said. "We must teach in ways that respect individual students and give meaning to their lives. And we must look poverty in the face and create the means for communities to address it at the same time as we work inside the classroom to give children joyful experiences that meet their natural curiosity and desire to learn."

Valens takes a long view of the march.

"I see this as the first part of a larger movement. I was active in the anti-war movement that eventually mobilized enough Americans to make it politically impossible to continue in Vietnam. So I know how long it can take to rouse people to a cause, especially in economic hard times."

No comments:

Post a Comment